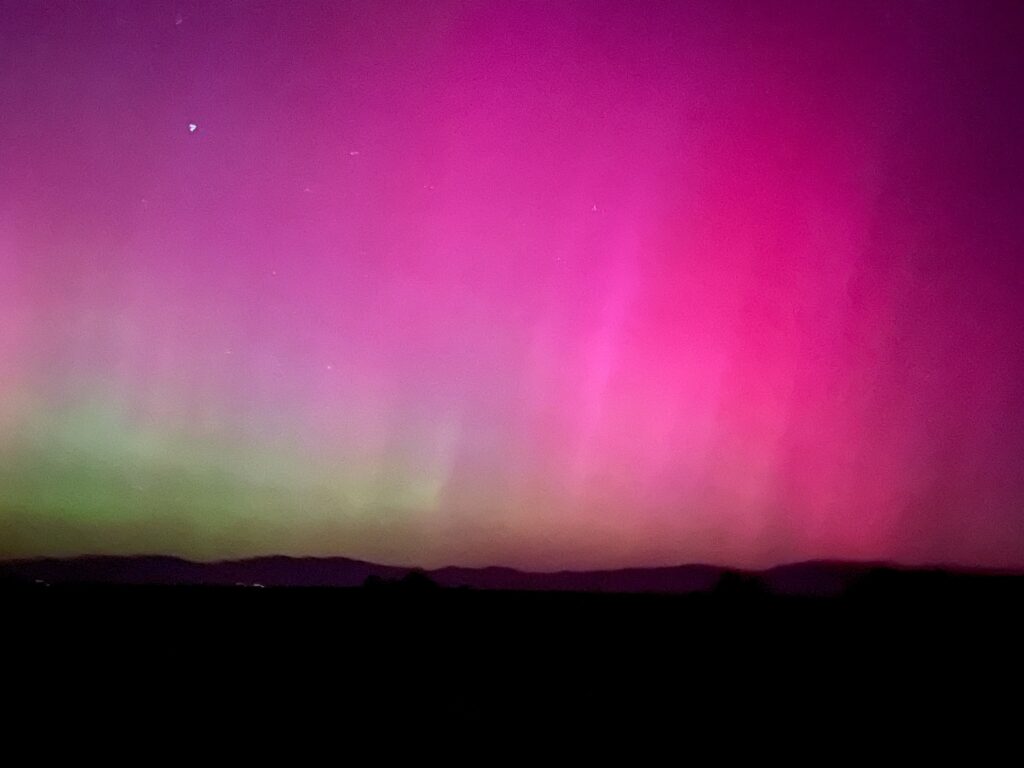

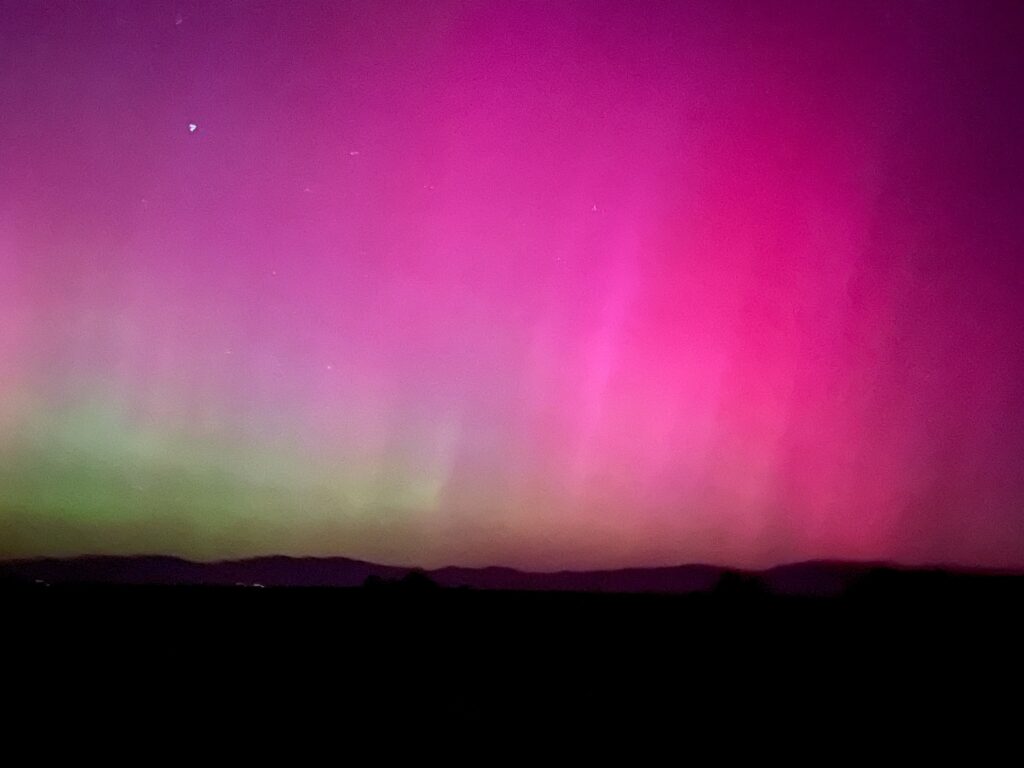

For many of us, this weekend provided a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see the Auroras, both Borealis and Australis, in all their glory. The astonishing colours lit up both the night sky and the internet for much of the weekend, with thousands of people flocking to vantage points to take photos.

While the auroras are a regular feature for those who live close to the poles, this weekend saw the displays extend further away than we’ve seen for more than 20 years, leading to a lot of questions about why this was happening and even to an alert from Transpower about possible adverse impacts on the electricity network. So what indeed was happening and what could this mean for the telco infrastructure?

In 1859, English astronomer Richard Carrington recorded the earliest observation of a solar flare. Carrington sketched what he saw – a series of dark splotches on the surface of the sun. What he didn’t know is that the sun had flung a ball of plasma at the planet that would hit in early September causing all the newly laid telegraph lines to spontaneous begin chattering to each other, overloaded with power from the sun itself.

This had never been recorded before, nor had it been a problem simply because we hadn’t started using electricity on this scale until quite recently. The sun’s ability to impact on our new-found technology hadn’t fully been appreciated.

*Aurora Australis 11th May 2024, as captured from Timaru, NZ by Janet and Trevor Karton.

The sun sits at the centre of our solar system and constantly throws out electromagnetic waves. We know them typically as heat and light and they helped create the conditions here on Earth for life as we know it to exist. But the sun also throws out energy in a somewhat haphazard manner and these intense, localised bursts are known as solar flares. Thanks to the magnetosphere – one of the upper layers in our atmosphere – these flares create pretty lights in the sky and have encouraged tourists to flock to places like Norway to see them in all their glory.

On top of that, occassionally the sun throws off big chunks of itself, in the form of plasma. We call these Coronal Mass Ejections (CMEs) and they contain huge amounts of energy. Most of these fly off into space but sometimes they come at us, here on the third planet. When they hit, they dump all that energy into the atmosphere and you can see tha Aurora from places all around the globe.

In March 1989 just such a solar storm hit Quebec in Canada. All that excess energy can cause power lines to overload. Those long lines of copper that make up our power grids are designed to transmit power regardless of the source, and when a sudden dump of it hits from the sky it can overload networks, trip the circuit breakers or worse, melt major parts of the network.

That’s exactly what happened in Quebec, cutting power entirely to the region. The storm took out power in other parts of the US and Canada and lead to a major rethink in the way power companies handle such things, but also in our need for monitoring capability.

These days there are multiple satellites in orbit both around Earth and around the sun that are constantly monitoring for such activity. We have advanced warning of anything major heading our way and there are even apps you can download that will alert you to incoming CME and solar flares.’

NEMA (the National Emergency Management Agency) also reports on activity through its Monitoring Alerting and Reporting centre which pushes out information to key agencies and organisations.

This is important because if we do get warning of something large heading our way we need to reduce the load on the power grid to as little as possible for the duration of the storm. Transpower issued just such an alert prior to the weekend, giving those of us who rely on electricity time to organise alternative solutions, such as generators to support critical telecommunications infraustructure, in case we need them. This weekend we didn’t, thankfully.

But impact on the electricity networks isn’t the only side effect from solar storms. Disruption to high frequency radio has long been a problem but there’s a more recent impact to consider. Heating causes things to expand, and when a large CME hits Earth, the atmosphere swells significantly. A large enough impact would pose a risk to low earth orbit (LEO) satellites which would suddenly find themselves operating as high-altitude aircraft, something they’re not really designed for. A big solar storm could knock out our new LEO satellite sector and potentially could also harm the GPS network.

On top of all that, if the storm is big enough it could damage the last bastion of the long-run copper lines in the telco market – the submarine cables. Submarine cables use copper lines to power repeater stations so they could be affected if the energy dump was large enough.

That’s a highly unlikely scenario but one we are considering as we work up our plans alongside Transpower and NEMA.

For now, if you want to know more about solar flares and CMEs, check out the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) website.

Paul Brislen is the CEO of the NZ Telecommunications Forum.